10 Ordibehesht/30 April

Some Thing Never Change…

Persian Gulf in the Ancient WorldPersian Gulf in theMiddle AgesThe Age of ColonialismPersian Gulf Naming DisputePersian Gulf affirmed as the standard name by the UNExtract from the latest UN paper from the Group of Experts on Geographical NamesFact sheet on the Legal and Historical Usage of the “Persian Gulf”Abusers of the NameTheArabian Gulf Google BombMaps of thePersian Gulf through HistoryPersian Gulf in the Ancient World Archaeological evidence suggests that Dilmun returned to prosperity after the Assyrian Empire stabilized the TigrisEuphrates area at the end of the second millennium B.C. A powerful ruler in Mesopotamia meant a prosperous gulf, and Ashurbanipal, the Assyrian king who ruled in the seventh century B.C., was particularly strong. He extended Assyrian influence as far as Egypt and controlled an empire that stretched from North Africa to the Persian Gulf. The Egyptians, however, regained control of their country about a half-century after they lost it.

A series of other conquests of varying lengths followed. In 325 B.C., Alexander the Great sent a fleet from India to follow the eastern, or Persian, coast of the gulf up to the mouth of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and sent other ships to explore the Arab side of the waterway. The temporary Greek presence in the area increased Western interest in the gulf during the next two centuries. Alexander's successors, however, did not control the area long enough to make the gulf a part of the Greek world. By about 250 B.C., the Greeks lost all territory east of Syria to the Parthians, a Persian dynasty in the East. The Parthians brought the gulf under Persian control and extended their influence as far as Oman.

The Parthian conquests demarcated the distinction between the Greek world of the Mediterranean Sea and the Persian Empire in the East. The Greeks, and the Romans after them, depended on theRed Sea route, whereas the

Parthians depended on thePersian Gulf route. Because they needed to keep the merchants who plied those routes under their control, the Parthians established garrisons as far south as Oman.

In the third century A.D., the

Sassanids, another Persian dynasty, succeeded the Parthians and held the area until the rise of Islam four centuries later. Under Sassanid rule, Persian control over the gulf reached its height. Oman was no longer a threat, and the Sassanids were strong enough to establish agricultural colonies and to engage some of the nomadic tribes in the interior as a border guard to protect their western flank from the Romans.

This agricultural and military contact gave people in the gulf greater exposure to Persian culture, as reflected in certain irrigation techniques still used in Oman. The gulf continued to be a crossroads, however, and its people learned about Persian beliefs, such as Zoroastrianism, as well as about Semitic and Mediterranean ideas.

Judaism and Christianity arrived in the gulf from a number of directions: from Jewish and Christian tribes in theArabian Desert; from Ethiopian Christians to the south; and fromMesopotamia, where Jewish and Christian communities flourished under Sassanid rule. Whereas Zoroastrianism seems to have been confined to Persian colonists, Christianity and Judaism were adopted by some Arabs. The popularity of these religions paled, however, when compared with the enthusiasm with which the Arabs greeted Islam.

Persian Gulf in theMiddle AgesIn the Islamic period, the prosperity of the gulf continued to be linked to markets in Mesopotamia and Persia.

Eastern Arabia was a center for both Kharijites and Shiites; in the Middle Ages, the

Ismaili Shiite faith constituted a particularly powerful force in the gulf. By the eleventh century, Ismaili power had waned. The Qarmatians succumbed to the same forces that had earlier threatened centers on the gulf coast--the ambitions of strong leaders inMesopotamia orPersia and the incursion of tribes from the interior. In 985 armies of the

Buyids, a Persian dynasty drove the Ismailis out ofIraq, and in 988 Arab tribes drove the Ismailis out of Al-Ahsa, an oasis they controlled in eastern Arabia. Thereafter, Ismaili presence in the gulf faded, and in the twentieth century the sect virtually disappeared.

The inland empires ofPersia (and Iraq) depended on customs duties from East-West trade, much of which passed by Oman. While the imam of Oman concerned himself with the interior, the Omani coast remained under the control of Persian rulers. The Buyids in the late tenth century eventually extended their influence down the gulf as far asOman. In the 1220s and 1230s, another group, the Zangids--based in Mosul, Iraq--sent troops to the Omani coast; around 1500 the

Safavids, an Iranian dynasty, pushed into the gulf as well. The

Safavids followed the Twelver Shiite tradition and imposed Shiite beliefs on those under their rule. Thus, Twelver communities were established inBahrain and to a lesser extent in Kuwait.

Oman's geographic location gave it access not only to theRed Sea trade but also to ships skirting the coast of Africa. By the end of the fifteenth century, however, a Persian ruler, the Shaykh of Hormuz, profited most from this trade. The Shaykh controlled the Persian port that lay directly across the gulf fromOman, and he collected customs duties in the busy Omani ports of Qalhat and Muscat. Ibadi imams continued to rule in the interior, but until Europeans entered the region in the sixteenth century, Ibadi rulers were unable to reclaim the coastal cities from the Iranians.

The Age of Colonialism During the Middle Ages, Muslim countries of theMiddle East controlled East-West trade. However, control changed in the fifteenth century. The Portuguese, who were building ships with deep hulls that remained stable in high seas, were thus able to make longer voyages. They pushed farther and farther down the west coast of Africa until they found their way around the southern tip of the continent and made contact with Muslim cities on the other side.

The Portuguese then extended their control to the local trade that crossed the Arabian Sea, capturing coastal cities in Oman and even some cities in Iran and setting up forts and customs houses on both coasts to collect duty. The Portuguese allowed local rulers to remain in control but collected tribute from them in exchange for that privilege, thus increasing Portuguese revenues.

The ruler most affected by the rise of Portuguese power was the Safavid shah ofIran,

Abbas I (1587-1629). During the time the Shaykh of Hormuz possessed effective control over gulf ports, he continued to pay lip service and tribute to the Safavid shah. When the Portuguese arrived, they forced the Shaykh to pay tribute to them. The shah could do little becauseIran was too weak at that time to challenge the Portuguese. For that the shah required another European power; he therefore invited the British and the Dutch to drive the Portuguese out of the gulf, in return for half the revenues from Iranian ports.

Both countries responded to the shah's offer, but it was the British who proved the most helpful. In 1622 the British, along with some of the shah's forces, attacked Hormuz and drove the Portuguese out of their trading center there. Initially, the Dutch cooperated with the British, but the two European powers eventually became rivals for access to the Iranian market. The British won, and

by the beginning of the nineteenth centuryBritain had become the major power in the gulf.

Struggles between Iranians and Europeans contributed to a power vacuum along the coast of Oman. The British attacks on the Portuguese coincided with the rise of the Yarubid line of Ibadi imams in the interior ofOman. The Yarubid took advantage of Portuguese preoccupation with naval battles on the Iranian side of the gulf and conquered the coastal cities of Oman around 1650. The imams moved into the old Portuguese stronghold of Muscat and so brought the Omani coast and interior under unified Ibadi control for the first time in almost 1,000 years.

A battle over imamate succession in the early eighteenth century, however, weakened Yarubid rule. Between the 1730s and the 1750s, the various parties began to solicit support from outside powers. The Yarubid family eventually called in an Iranian army, which reestablished Iranian influence on the Omani coast.

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were a turbulent time for Arabia in general and for the gulf in particular. To the southeast, the Al-Sa’id of Oman were extending their influence northward, and from Iraq the Ottoman Turks were extending their influence southward. From the east, both the Iranians and the British were becoming increasingly involved in Arab affairs.

Persian Gulf Naming DisputeSince the 1960s, there has been movement in some Arab countries to refer to the Persian Gulf as the "Arabian Gulf", and it has become an ongoing naming dispute.

In possibly every map printed before 1960 and in most modern international treaties, documents and maps, this body of water is known by the name "Persian Gulf", reflecting traditional usage since the Greek geographers Strabo and Ptolemy, and the geopolitical realities of the time with a powerful Persian Empire (Iran) comprising the whole northern coastline and a scattering of local emirates on the Arabian coast. But by the 1960s and with the rise of Arab nationalism, some Arab countries, including the ones bordering the Persian Gulf, adopted widespread use of the term "Arab Gulf" to refer to this waterway; this is the standard usage in modern Arabic. This coupled with the decreasing influence of Iran on the political and economic priorities of the English speaking Western World led to increasing acceptance, in regional politics and the mostly petroleum-related business, of the new alternative naming convention "Arabian Gulf".

Until the end of the 19th century, "Arabian Gulf" has been used to refer to what is now known as the

Red Sea. This usage was adopted into Europeans maps from, among others, Strabo and Ptolemy who called the Red Sea,

Sinus Arabicus (Arabian Gulf). Both of these Greek geographers reserved "Persian Gulf" to refer to the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. In the early Islamic era, Muslim geographers did the same,Bahr Faris= Persian Sea orKhalij Faris= Persian Gulf. Later, most European maps from the early Modern Times onwards used similar terms (Sinus Persicus, Persischer Golf, Golfo di Persia and the like, in different languages) when referring to the Persian Gulf, possibly taking the name from the Islamic sources. For a short while in the 17th century, the term "Gulf of Basra" was also being used, which made a reference to the town of Basra (Iraq), an important trading port of the time.

The matter remains very contentious, in particular as the competing naming conventions are supported by respective governments, in internal literature, but also in dealings with other states and international organizations. Some parties with certain aims use terms like "The Gulf" or the "Arabo-Persian Gulf"!!!!!.

Persian Gulf affirmed as the standard name by the UNThe United Nations on many occasions has requested that only Persian Gulf be used as the standard geographical designation for that body of water. Most recently, the UN Secretariat has issued two editorial directives in 1994 and 1999 affirming the position of this organization on this matter.

In 2004, the National Geographic Society published a new edition of its

National Geographic Atlas of the World

using the term "Arabian Gulf"as an alternative name (in smaller type and in parentheses) for "Persian Gulf". This resulted in heavy protests by many Persians (Iranians), especially the Internet user community, which led to the Iranian government acting on the issue and

banning the distribution of the society's publications in Iran. On December 30, 2004, the society reversed its decision and published an Atlas Update, removing the parenthetical reference and adding a note: "Historically and most commonly known as the Persian Gulf, this body of water is referred to by some as the Arabian Gulf." It also removed the alternative Arabic names for certain islands and/or replaced them with Persian ones.

Some atlases and media outlets have taken to referring to "The Gulf" without any adjectival qualification. This usage is followed by The Times Atlas of the World.

Extract from the latest UN paper from the Group of Experts on Geographical Names: Historical, Geographical and Legal Validity of the Name: PERSIAN GULF (4 April 2006): Background for Application of Incorrect Words Instead of PERSIAN GULF.After England's attack on Khark Island in 1837, the government of Iran at that time protested to England's separatist policy in the PERSIAN GULF and officially warned the government of Britain to avoid mischief intended at separating the southern side of Iran. This warning caused the Times Journal, published in London in 1840, to

name the PERSIAN GULF for the first time as Britain Sea, but such a name never found any place.Moreover, following nationalization of the oil industry in Iran in 1950 and dispossession of English Companies and discontinuation of relations between Iran and England, the Ministry of English Colonies, for the first time used the incorrect name of this water body. In these years, the States South of the Persian Gulf were either colonies of Britain or under its support. To compensate its defeat, the government of England published a book by

Roderick Oven, an agent of English Spy Org., in 1957 which was immediately translated into Arabic. In this book the assassination of the name PERSIAN GULF began and in 1966, Sir Charles M. Belgrieve, the political agent of England in the affairs of Persian Gulf Southern States supported by England, published a book at the end of his mission named:Golden Bulbs at Arabic Gulf. After coup of Abdolkarim Ghasem in 1958 in Iraq and then coup byBa’ath Party and their claims for some lands against Iran, they avoided using the name of PERSIAN GULF for political reasons.

In 1960, after Iran and Egypt's disconnection of relationships and after the Arab-Israeli war, anti Iranian actions culminated due to the previous Iranian regime’s support of Israel. This occurred in Arabic Circles and in a congress of Ba’ath Party convened at Damascus, in which participating heads demanded for change of the name of PERSIAN GULF to the forged name of Arabic gulf, without relying on any legal and historical document. Following this, to achieve the political motive, they altered this historical name in the text books of Arabic Countries.

After the Islamic Revolution, followed by breaking relations between USA and Iran, and commencement of the imposed war of Iraq against Iran, there have been some efforts to apply incorrect words instead of the Name Persian Gulf. Most of these efforts were not on purpose but resulted from unawareness of facts.

Though, in USA the geographic and publication institutes have been hardly influenced by other countries, but in 2005, we witnessed that the reputable National Geographic Society, with a past history of not accepting and using forged words in its works, distorted the name of PERSIAN GULF and Iranian islands and intentionally mentioned incorrect information.

This action only helped damaging its own international credibility, but ultimately, it surrendered to protests of Iranians throughout the world and corrected its error.It is interesting that Mr. Roderick Oven stipulated in Golden Bulbs at Arabic Gulf: "I visited all parts of PERSIAN GULF and believed that it was Persian Gulf, because I noticed no map or deed, unless it had named the place as Persian Gulf, but when I watched it closely, I found out that the people residing at the southern beaches are Arabs, therefore, to be polite, we should name it: Arabic Gulf."

Either Mr. Roderick Oven should have noticed that on the northern sector of that water body, up to 1269 km of coast exists with a far larger population who speak Farsi. This is larger than the Arabian population he was concerned about. He did not notice the important fact that this sea was first named by the Greeks and neither Iranian nor Arabs took any part in it. The Muslims and Arab Geographers learned the names from the Greeks and Romans, and used it in their works, especially that they named Pars Sea, unanimously: Persian Gulf.

In the end, it is worth mentioning that the name of Persian Gulf has been admitted in all the live languages of the world so far and all the countries throughout the world, name this Iranian Sea, just in the language of the people: PERSIAN GULF.

Fact sheet on the Legal and Historical Usage of the “Persian Gulf”International Legal Standards· The Group of Experts on Geographical Names was set up by the Secretary-General of the

United Nations in pursuance of the Economic and Social Council resolution 715 A (XXVII)

of

23 April 1959, and has endorsed “Persian Gulf” as the official name of the body of water.

· The Eighth United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names

Berlin,

27 August-5 September 2002, E/CONF.94/CRP.87, Item 17 (a) of the provisional

agenda, has based its decision of the discussion of “Arabian Gulf” versus the “Persian Gulf”

on the reference “TOPONYMY, The Lore, Laws and Language of GEOGRAPHICAL

NAMES”, by Naftali Kadmon Vantage Press Inc.,New York, 2001, 333 pp., 35 illustrations,

ISBN 0-533-13531-1, Chapter 8 “Persian Gulf orArabian Gulf”?, which argues that the use

of “Arabian Gulf” is faulty. The United Nations website only uses the term “Arabian Gulf”

when presenting transcripts of speeches by Arab delegates.

· The United Nations Oceans and Law of the Sea Office uses only the term Persian Gulf in its

legal documents.

Historical Maps of the RegionStarting from the earliest maps, the body of water has been called Persian Gulf by European sources. Among the first Atlases in the world is that of Jean Baptiste Anville, 1751. This map of westernAsia shows the body of water labeled as “Golfe Persique” orPersian Gulf.

Abusers of the Name:A Gulf University

Aramco

Asia-Soccer

British Airways

BBC

HarperCollins Publisher

Hyatt Hotel

National Geographic

Olympic Airlines

Platts

Reuters News

Simpsons Spence and Yong

Worldscale Association (London &New York)

TheArabian Gulf Google BombThe most successful Google bomb on the internet to date would certainly have to be the now famous

Arabian Gulf bomb. This was the combined efforts of hundreds of bloggers, webmasters and Persian forums who pointed links with the wordArabian Gulf to a spoof error page found at

www.arabian-gulf.info.

It all started with a single blogger, the Lego Fish, who, after the outrage of the global Iranian community and indeed even the Iranian government over the National Geographic's disgraceful act of printing "Arabian Gulf" in brackets underneath the one true name for this important waterway, suggested that the online community of Iranians retaliate by "Google Bombing" the words Arabian Gulf.

The first spoof page was set up at

http://www.legofish.com/arabian_gulf.htm. Within hours, dozens of bloggers had taken up the campaign and linked to this page. Within days, hundreds of Iranian websites, weblogs and Forums had linked to it.

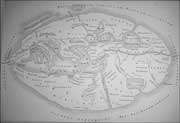

Maps of thePersian Gulf through HistoryWorld map from Ptolemy, Geographia. Venice: J.Pentius de Leucho, 1511

Gerhard Mercator's atlas production in 1578 from Ptolemy's Geographia clearly depicting Sinus Arabicus(today's Red Sea) and Persicus Sinus (Persian Gulf)

Map of Persia, by John Tallis, ca.1851

Arabic Map of the Persian Gulf, by Arab scholar Dr. Hassan Ibrahim Hassan from his book "Political History of Islam" in Arabic. Published by Hejazi Printing House, Cairo, 1935Map of the Islamic Empire, Sobhi Abdul- Karim,Cairo, 1965

Arabic Map of Saudi Arabia, Map Art USA, 1966

Taken from:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persian_Gulf_naming_dispute http://web.mit.edu/isg/persiangulffactsheet.pdfhttp://www.davidrumsey.com/index.html

http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Geography/persian.gulf/persian_sea.htm http://www.geocities.com/prsn_gulf/