AB-ANB?R History

Part 1

AB-ANBAR “water reservoir.”

i. History

The term Ab-anbar is common throughout Iran as a designation for roofed underground water cisterns. In Turkmenistan the term sardoba is found for similar structures (see, e.g., N. S. Grazhdankina, Stroitel’nye materialy sardob Turkmenistana, Izvestiya Akademii Nauk Turkmenistanskoi SSR, 1954, no. 4; G. Pugachenkova, Puti razvitiya arkhitektury yuzhnogo Turkmenistana pory rabovladeniya i feodalizma, Moscow, 1958, pp. 243, 394). Early Islamic sources in Arabic appear to use the words estakr for a covered tank or cistern (Le Strange, Lands, pp. 276, 285); and in 14th to 16th century texts, can be understood as designating a cistern (Jame al-Kayrat, p. 28; Vaqfnama, p. 875; Tarik-e jadid-e Yazd, p. 129).

The Ab-anbar was one of the constructions developed in Iran as part of a water management system in areas reliant on permanent (springs, qan?ts) or on seasonal (rain) water.

A settlement’s capacity for storing water ensured its survival over the hot, dry season when even the permanent water supply would diminish. Private cisterns were filled from qan?ts (man-made underground channels) during the winter months before the floods, while surplus flood water could often be stored in open tanks, as well as in the large, public, covered cisterns (Wulff, Crafts, p. 258; Pugachenkova, Puti, p. 243). Water was brought to the cisterns by special channels leading from the main qanat or holding tanks and was controlled by sluice gates. The Ab-anbar, a ventilated storage chamber, could then provide cool water throughout the summer months. Often rooms or pavilions were built within the complex of the cistern to provide a comfortable resting place as well.

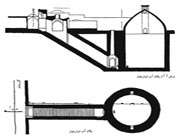

While private houses may have had their own cisterns, filled in turn from the qanats or streams, in desert towns like Yazd or Aabas the more noteworthy and elaborate structures were built for public use, often as part of a vaqf, within towns as well as on caravan routs (see e.g., A. U. Pope and E. Beaudouin, “City Plans,” in Survey of Persian Art, pp. 1391-1410). Two types of structures have been noted, a cylindrical reservoir with a dome and a rectangular one supported by piers or pillars (see M. Siroux, Caravansérails d’Iran et petites constructions routiers, MIFAO, Cairo, 1949). Each was marked by a portal, often with an inscription giving the name of the benefactor (builder or repairer) and the date. The portal opened into a steep, barrel-vaulted passageway, leading down to the reservoir.

Although a detailed study of all variations of construction techniques of the Ab-anbar in Iran still remains to be done, Grazhdankina’s analyses of similar structures in Turkmenistan, as well as observations by Beazley, Wulff, Siroux, and Sotuda (see below), allow a general outline of the technique. The prime objective in constructing an Ab-anbar is to provide a totally waterproof container for a large volume of water while allowing for proper ventilation and access. The excavation was lined with overfired brick set into a sand and clay mixture. It was then covered with a layer (about 3 cm) of waterproof mortar, saruj (see Grazhdankina, Materialy, for specific analyses of the mortar). Larger cisterns were often lined with an additional double layer of bricks, covered with another layer of saruj of slightly different composition, and finished with a hard plaster coat.

To be continued ...